Redesign Democracy

A Better Solution for the Digital Era

Introduction

Older generations seem to chronically lament that the world of the young is new, unprecedented, and terrible. Nostalgia and familiarity combine to create a “They don’t make ‘em like they used to…” mentality, one that ignores the fact preceding generations were saying exactly the same thing about them. The reality is that things are the way they are, each of us typically being more comfortable with and connected to that which we know the best and identify most closely with ourselves.

However, it is just possible that we are reaching the nadir of the existing democratic process in the United States, an environment of toxicity and partisanship that shows no sign of softening. Coincidentally we are also at a moment where technology enables the tantalizing potential to reconsider the way our government is structured.

Democracy in the United States has over 200 years of history behind it; democracy as a government system has more than 2,000 years of precedent. It may be the best system going but it sure doesn’t seem to be doing a very good job. It might even be obsolete in this world that looks so very different than the one which produced it.

This is the moment - our moment, together, yours and mine - to create a better system. So read on, see what I have in mind, and why. And if it sounds good to enough of us, maybe we can really change the world.

Dirk Knemeyer

Granville, Ohio, U.S.

September 8, 2014

This article is also available as PDF, eBook, and spoken by the author free of charge.

Request a CopyThe Origins of Democracy

Today's U.S. government is built on principles and practices established more than 2,000 years ago. Can digital technology help us realize a better way?

Democracy first took root around 508 BCE in Athens, Greece, the cultural cradle of antiquity. From 508 to 146 BCE Greece, particularly Athens, set the foundation upon which western civilization was to develop. Much of modern science, art, and architecture traces directly back to this place and time, building off of or reacting to the achievements of this period over the subsequent 2,160 years. This is certainly the case with modern democracy.

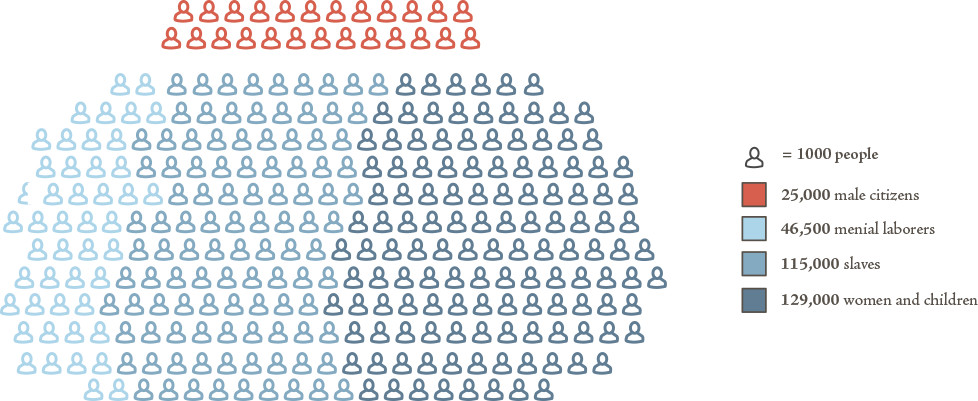

Of course, the Athenians had a very different conception than we do of who was eligible to rule, to say nothing of who could vote. According to A.W. Gomme, of the estimated 315,500 people in Athens during the height of their civilization, there were:

Key technologies from ancient Greece: thermometers, coin money, and catapults.

Only the 25,000 male citizens of Athens could vote, meaning that fewer than 13% of the population had the privilege to choose their leaders.

The lack of universal representation was obviously a problem, but a more subtle issue with Athenian democracy was the scale. In their very different and dispersed representational model - with dozens of roles - more than half of the 25,000 male citizens served in some official governing capacity at all times. The consequence was that most of this privileged class participated in government or had direct relationships and access to those who did.

We continue to model our government systems on the same democratic approach, established more than 2,000 years ago, which represented only a small, privileged minority. Is democracy a mistake?

Systems of government are characterized by a broad and complicated range of characteristics. This complexity can make it difficult to consider new political systems. Over the last 3,000 years the developing world has tried hundreds of different systems of government, many of which fall under the archetypes presented here. It is valuable to consider them in thinking about how we can re-imagine our own governance. However, we live in a moment when human rights are of paramount importance, so governments that minimize citizen involvement in determining laws and leadership present a less attractive choice.

The reality is, at our current evolutionary stage, people must advocate for themselves. Time and time again we’ve learned that trusting someone or something else with our own well-being generally leads to its degrading. It is, after all, human nature to value one’s own needs over those of society at large.

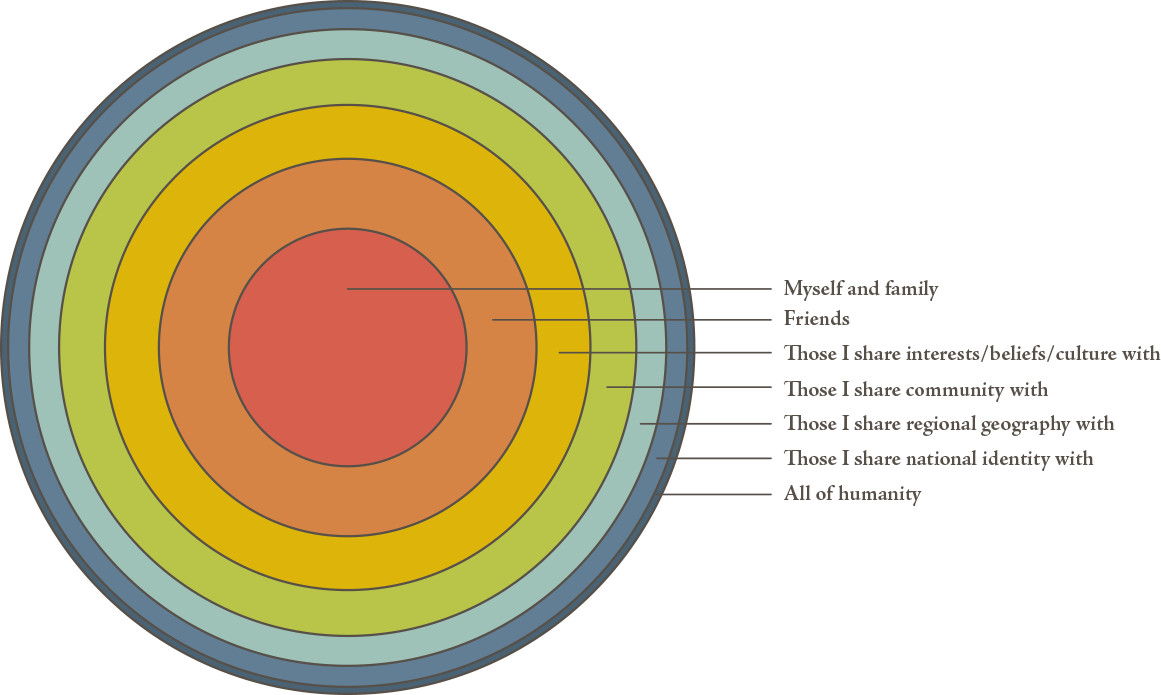

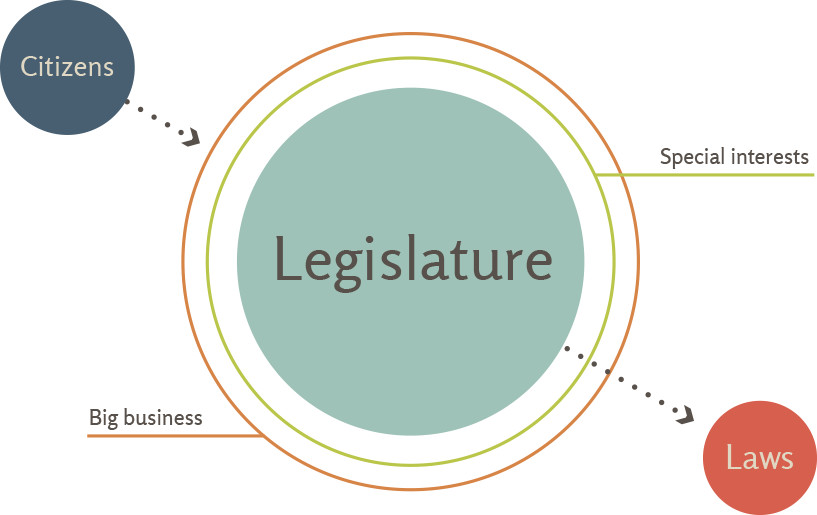

The way we take care of our needs can be described by a series of concentric rings.

“It has been said that democracy is the worst form of government except all the others that have been tried.” — Sir Winston Churchill

Each ring out from the center gets less of my care and interest. I am just one person who has an intricate life to manage, one that precludes me from impacting the world far beyond my own immediate interests. Extrapolate that to the leader of a nation-state needing to care for all citizens equally. It is a literal impossibility. At its extreme, such natural self-interest may manifest as corruption, but for most managing that self-interest is simply one of the challenges that leaders must face.

“It has been said that democracy is the worst form of government except all the others that have been tried.” — Sir Winston Churchill

Given that people are naturally self-focused, and that human rights are an essential aspect to a modern government system, I will focus on redesigning democracy as opposed to changing to a different form of government. By giving citizens direct influence over their laws and leaders we give them the greatest degree of control over their own well-being. Perhaps our redesign of democracy can extend the degree of self-control and agency afforded by the US government of today. The question is, how can we move the government decisions that influence us closer to the centers of our own circles?

Elements of a Better Democracy

One of the inherent flaws in modern democracies is the large size of contemporary nation-states. The bigger a group of people, the more removed those at the top will be from best serving some significant percentage of those at the bottom. There is too diverse a set of needs, values, beliefs, and affiliations for everyone to be properly taken care of. In the United States, this problem is exacerbated by a highly heterogeneous population. While there are many benefits to the “melting pot” —social, genetic, and philosophical, to name a few— the very diversity that provides strength also makes it harder for each individual to be properly governed. In a perfect world our society would cater to each of us as a unique person with idiosyncratic needs, woven nicely into the larger social fabric. The reality of a nation with hundreds of millions of people is that the larger and more diverse it is, the less customized to individual needs and desires the experience of being a citizen will be.

These ideas are built on four basic premises:

Other first-world nations with similar civil rights but higher well being and happiness than the United States have a much healthier fiscal outlook. For example, their citizens may pay more than 50% of their income in taxes, or provide mandatory military service, or save significant proportions of their income instead of spending beyond their means. Meanwhile, citizens of the United States spend more minutes per day on average watching television than any other nation. Instead of excercising our right to watch the most minutes of televison per citizen each day than any other nation, perhaps we could do more to give back to the country and system that provides our many liberties and benefits. Each dollar cotributed in taxes, or each hour spent in some form of civil service, strengthens the nation as a whole. It creates a cycle of success.

-

Citizenship should provide major benefits and carry significant responsibilities. In the United States, the benefits of citizenship have never been more uncertain. We have the most extensive national security in the world, a clear benefit even if it is an order of magnitude larger than it needs to be. The recent adoption of “Obamacare” begins to move us closer to our first-world brethren from a health and wellness perspective. Social security and other social welfare programs are under threat both financially and legislatively, possibly removing a key personal security perk from our lives. US citizens enjoy benefits well beyond most of the world, but no better than the top half of first-world nations. Though some might argue that Athenian citizens had a more lavish lifestyle, relatively speaking, than most Americans do today, the cost of that lifestyle was borne by the majority of Athenian residents—all considered non-citizens. By contrast, even the vast majority of Americans who are not 1%’ers enjoy the status of citizenship regardless of gender, race, age, or place of origin, and can aspire to nearly all of the same privileges.

However, our nation asks very little of us in return. Other than pay taxes, which are among the lowest in the wealthy first world, and follow the laws, which are among the most liberal and individual-freedoms-friendly for a large nation-state in human history, we have little responsibility to our nation, state, community, or fellow citizens. All we need to do is be born and try not become a fringe part of the society, such as a felon. Those not born as United States citizens have a process to follow, but one that is barely more rigorous than simply moving here and living a good, normal life.

Getting a lot for a little might seem like a good deal, but it is not good for our country nor for ourselves. From a pragmatic perspective, our low taxes contribute to what is now over $17 trillion in debt. Our general lack of other societal responsibilities not only contribute to that debt - we could be contributing time or effort in small ways that would mitigate our collective debt) - they also give us a sense of entitlement. Feeling entitled can lead to selfish, lazy, and even anti-social behavior. These negatively impact health and well being, plus contribute to societal waste and personally motivated short-term thinking.

By injecting more citizen responsibility, or at least productive participation, into our democracy we can curb unhealthy individual and collective behaviors while increasing prosperity for everyone.

Josef Stalin famously instituted five-year plans, a model that saw the Soviet Union centralize and modernize at a prodigious rate. Copied by Nazi Germany (successfully) as well as Communist China (less successfully) this set of strategies and tactics enabled rapid growth. While these successes were admittedly reached through brutality and civil rights abuses, it is indisputable that by setting a broad agenda that strategically brings together many disparate elements of a nation for single purpose, profound change can be achieved.

-

We need unifying initiatives to guide our government. From a philosophical perspective we already have these: the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution, and the Bill of Rights. However, on an operational level we do not. Every four years there is a new presidential election. Every two years we elect our representatives, every six, our senators and state governors. By the time any of these civil servants gets comfortable in office there is little time to think broadly; before long they need to worry about earning future votes to win the next election and maintain their position.

Each time there is a change it potentially stops and even reverses the initiatives instigated by the previous regime. In part this is good: it provides the checks-and-balances so essential to democratic law. However, it also creates significant inefficiency. The trillion-dollar initiative of the current Administration will be the first target for the opposition party if control changes hands after the next national election. If there were a list of initiatives that gave us mandates over longer periods of time, a decade, two decades, or even more, we could borrow some of the key executive benefits of monarchical or dictatorial regimes while maintaining a true democracy.

-

Citizens should have a closer, more direct relationship with their leaders and laws. While the majority of residents of ancient Athens were likely not citizens, those who were had a direct relationship to the workings of their “national” government. This is an ideal that gives people the greatest input into their government’s functioning, necessarily putting the individual’s rights and perspectives close to the decisions being made for and about them. It means participation.

What if an amendment to the U.S. Constitution required an audacious, strategic long-term goal that we would commit to achieving regardless of whatever else might happen? President John F. Kennedy tried this on an ad hoc basis and - seemingly beyond the bounds of reason - we found ourselves on the moon less than a decade later.

-

Laws and leadership should have a proper balance of long-term and short-term planning. China’s emphasis on long-term planning turned them into a global superpower around the turn of the 20th century. By contrast, for decades the US government has pursued plans that are painfully overbalanced toward short-term thinking. This is reflected in everything from our financial position to our energy policy. While the reasons for this are complicated, one key aspect concerns politicians pandering to their voter base, advocating the knee-jerk whims of a limited constituency to the detriment of the nation as a whole. As well, there is the binary nature of compromise in an entrenched two-party system. How can we shift to a model that values long-term planning in ways more similar to our Chinese friends?

Issues with the Legislature

Our democratic system features a separation of powers on the national level, split between executive (the President), legislative (Senate and House of Representatives) and judicial (Supreme Court) branches.

A nation ultimately needs one empowered decision maker. While theoretically it could be a group of people instead of an individual, historically this “decision by committee” model has not worked well. The separation of powers is designed to allow the executive branch some appropriate degree of autonomous control. Each citizen votes individually on the President. The outcome of the vote is intended to represent the majority’s choice.

Appointees to the Supreme Court are nominated by the President, confirmed by the Senate, and serve for life. The idea of a Supreme Court and life appointment are sensible. While my broader ideas would impact this process somewhat the existence and role of the Supreme Court—determining the rule of law at the highest judicial level— is an important foundational one. They can stay.

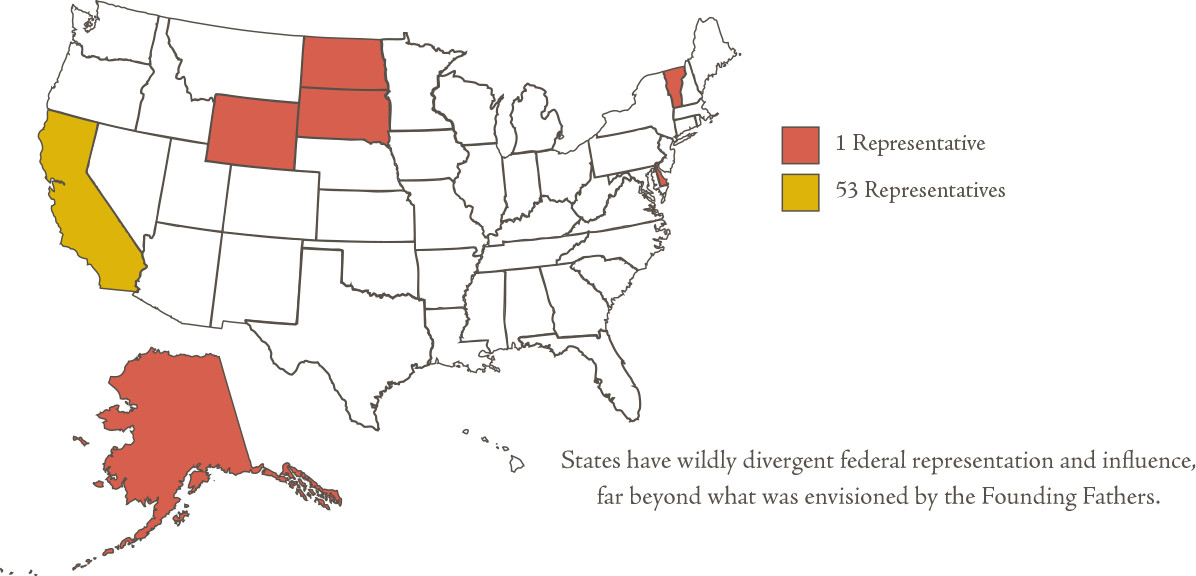

Which brings us to the problem of this particular solution: the legislative branch. Each state is represented by two Senators and a variable number of State Representatives, ranging from 53 (California) to just one (six states). This configuration goes back to the original U.S. Constitution, some 227 years ago.

With legislators like Eliot Spitzer, John Edwards, and Charles Keating, who needs enemies?

While the numerical structure of the legislature is problematic, there are bigger issues:

-

Senators and Representatives are not necessarily qualified to participate in making laws. Their only qualification is having been picked by constituencies made up of people who, for the most part, know them only from advertising and marketing and what their local paper chooses to write. So, the lawmakers may have questionable qualifications and the people who choose them are largely ignorant as to their efficacy for the position.

| Lawyers | 32.5% |

| Businesspeople | 24.4% |

| Career Politicians/Government Employees |

12.0% |

| Educators | 9.6% |

| Medical Professionals | 6.0% |

| Career Military/Law Enforcement | 4.1% |

| Farmers & Ranchers | 2.8% |

| Nonprofit & Community Workers | 2.6% |

| Entertainment & Media | 1.9% |

| Accountants | 1.3% |

Composition of 113th Congress

| Engineers | 0.6% |

| Social Workers | 0.6% |

| Clergy | 0.4% |

| Carpenter | 0.2% |

| Legal Secretary | 0.2% |

| Microbiologist | 0.2% |

| Mill Supervisor | 0.2% |

| Physicist | 0.2% |

| Union Rep | 0.2% |

| Youth Camp Director | 0.2% |

As of Wednesday, March 19, 2014 House Majority Leader John Boehner had raised $5,408,271 toward his re-election from contributions outside the state of Ohio. This equates to a whopping 87.9% of his total contributions being from people and organizations other than those he is geographically elected to represent. Source: OpenSecrets.org

-

Legislators are incentivized to focus their lawmaking efforts on decisions that will feed into their re-election. That means they may be rewarded to ignore questions of the whole for pandering to their few. While the few may need an advocate in the arena of the many, legislators must remain mindful of the bigger picture.

-

Legislators can put a great deal of space between the individual citizen and themselves. Remember the concentric circles I talked about? The random citizen is of very little practical concern to the legislator. They may genuinely intend to advocate for all of their people but it is only human nature that we privilege those to whom we have more connection. In the case of legislators, that can often be special interests and big companies as opposed to individual citizens.

I’m actually sympathetic to much of government corruption. Are you going to try and get that big contract over to your friend, or to a stranger at your friend’s expense? Some certainly have the discipline to adjudicate these situations fairly, but they are the exceptional ones in acting contrary to human nature. Would you, truly, risk hurting people you know and care about in such a situation? So long as the legislators are representing tens of thousands of people some will be privileged to the detriment of others.

The bottom line is that this is no way for the legislative branch of our government to be organized. No other alternative seemed possible in the 18th century because there was no practical way for the average citizen to participate directly in government.

Today, thanks to digital technology, that is no longer true.

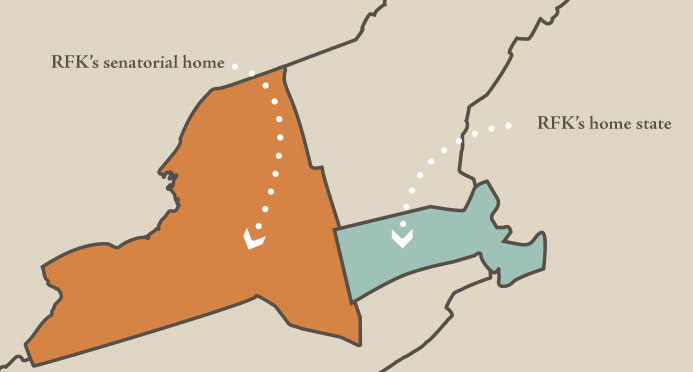

National politicians routinely “carpetbag”: owning a residence in a district or state in which they do not reside in order to run for Congress or, particularly, the Senate. Prominent examples include Robert F. Kennedy (New York Senate, 1964); Rick Santorum (Pennsylvania 18th Congressional District, 1990); Hillary Rodham Clinton (New York Senate, 2000)

Here is the basic model of the current legislature.

-

A few citizens in a voting district of thousands or millions of people compete to be elected as Representatives and Senators. There is a strong correlation between the amount of money a campaign spends on advertising and whether the candidate is able to win the election. At times national special interest groups spend tremendous amounts of money to control the outcome in local elections.

-

All citizens in a voting district have the opportunity to choose their Senators and Representatives. Their choices are generally based on minimal information, primarily advertising and local media endorsements as well as the political party of the candidate. Less than 1% of voting citizens will ever meet these legislators, much less have an in-depth conversation with them.

-

Senators and Representatives write and vote on laws. They are influenced by their constituents, special interests, and lobbyists, as well as by other members of their political party who have little investment in the constituency of others. Over $3.3 billion dollars are spent on lobbying to influence policy in the United States each year. (Source: Center for Responsive Politics) And less than 10% of bills introduced in the 112th U.S. Congress—561 of 6,845—actually passed into law. (Source: Brookings)

-

Every six years (Senators) or two years (Representatives) the legislators are up for re-election. Since 1964 the House of Representatives has boasted a re-election rate of over 90%. While serving as Senators and Representatives, our legislators spend substantial time and effort attempting to get re-elected in lieu of performing their duties.

There’s a lot that is broken about this system, and that is only an overview that doesn’t get into its more limited but far darker underbelly of scandals and graft.

The Digital Solution

As of January 2014 58% of U.S. adults already own a smartphone.

It all starts with the smartphone. This miraculous device gives us the power of a computer in our hand, pocket or purse at all times. It enables any citizen to receive information in and communicate out, both in real-time while running software applications far more powerful than those being run on desktop computers just a decade ago. The easy availability to such powerful, real-time technology empowers us to radically re-think each individual’s role in our collective governance. No longer is there a limitation of space and time to prevent our getting high-resolution information on our government and legislators. There is no barrier to our placing a secure, verified vote on a candidate or law from the comfort of our home. The majority of Americans now hold in our hand the power to do everything that our legislators do when they vote on a bill: read the text. Consider outside information. Engage in debate or conversation. Place the vote. It’s no different from a use case perspective than how we use Facebook. The difference is, rather than our time being spent on pleasant conveniences we are able to influence our nation as the self-representational government that democracy purports to be.

We’re not accustomed to thinking about having visibility into and knowledge of the inner workings of our nation, state, and locality, much less direct impact on decisions. But we can. And we should.

The award-winning Arlington Visual Budget, conceived and designed by GoInvo, is an exemplar of a progressive local community providing transparency into key aspects of their government.

Click to learn more

Given the unprecedented ability our citizens now have to be more actively and directly engaged in our government, here is my suggestion for reconceiving the legislature into one more reflective of the philosophies underpinning democracy:

-

The current senators and representatives would all be removed and replaced with exceptional individuals chosen for their potential to contribute to an enlightened government. Economists, physicists, biologists. Experts in well-being, personality, healthy communities. Labor leaders. Structural engineers. Agriculturists. Basically, if you look at every Presidential cabinet role, and all of the different aspects of life that bills under current consideration touch, experts that pertain to all of those things would be represented. So instead of the key qualification for participating being to influence voters and pacify lobbyists, our legislative branch would be filled with the brightest minds, the most insightful souls, and our leading experts. Yes, there would need to be some “politicians” among them—people who can build consensus and write legislative actions. But they should simply be one of the many roles being filled in this group of experts, not the vast majority of the chamber. While the initial group would need some kind of blanket appointment - nominated by the president, confirmed by popular vote? - eventually they would stay or go based on their statistics: are they contributing to successful legislation? If yes, then great. If not, then the executive branch would nominate new candidates who would be confirmed via the general voting system.

Similar to the legislators of old, these people would introduce ideas and work together to bring bills forward. However they would not be doing the voting: we, the people, would. And, they would be engaged in far more valuable long-term strategic planning. This collection of the best and brightest tasked with leading the future of the country would not be thinking about pacifying Joe Smith in Tuscaloosa. They would need to consider and care for all of our citizens, and lead us down a path that took care of Joe Smith in more indirect ways. They would impact our lives by moving us away from the immediate chatter and into systems and trajectories intended to make the most of our potential. So not only would we be replacing potentially unqualified people with supremely qualified people, their charter would change. They would be far more motivated by the greater and collective good than the politicians in Washington who, as of this writing, have a 10.8% approval rating. (Source: RealClearPolitics)

-

Independent of the government itself, a new profession of “analysts” would be required. Many of these would likely come from the current ranks of political commentators but would surely attract a new breed of personalities as well. Their role would be to represent a very specific position—it could be as narrow as “Protect the second amendment at all costs” or as broad as “Advocate for individual liberties.” They would review every bill, comment on it, and make a recommendation to vote for or against. Voters would “subscribe” to them. That subscription might be free, or the analyst might charge for it. But they, and whatever staff they developed, would be helping to guide people as to what bills deserve to be voted on or not, based on the beliefs and interests of each voter. Instead of blasting their platform out in a broadband way their platform would be taken for granted and they would be informing voters as to how they should vote based on their stated beliefs and interests.

Now, it is unavoidable that the same lobbyists and special interests that infect our legislators and media will also play a big role with the analysts, as well as the experts who are the actual legislators. This is unavoidable. However, experts who are already successful, recognized, and accomplished in their particular fields will be far less susceptible to lobbying influence than the politician who gets through the voting gauntlet. The analysts are may be a different story, but the beauty is that the system as a whole comes back to the voters in a fully democratic way. It is responsive. Analysts may be corrupted in all kinds of ways, but if the voters stop subscribing to them they will not be relevant anymore. It is far harder for special interests to invest in this kind of brittle resource than putting millions into a senator who, excepting a scandal, will be around for six years.

-

Voting currently done by legislators would instead be conducted directly by citizens. People could choose to use their existing smartphone, or be issued a very basic device for just the purpose of democratic participation. There would be small local voting centers also available in cases of lost or damaged voting devices. Each day, or week, or whatever the correct frequency is, citizens would receive a digital packet to review. Each bill would include a summary and the recommendation of all the analysts they subscribe to. Drilling in would let them see the entire bill with annotations from their analysts, or longer analysis about the bill. Citizens would have, at their fingertips, everything required to vote on their own behalf.

This is true democracy. The abstractions in the current process that leave us with a stable of professional politicians sporting a wide variety of qualifications is a relic of the analog world. Well, thanks to digital technology, that system is redundant. We can share information in real time. We can provide a secure vote via our devices. We can easily evaluate success via an objective system and judge the actors in democratic rule with those metrics. It seems so radical, yet the only thing that is radical to me is why we aren’t already talking about it.

Would our legislature have benefited from Stephen Hawking participating? Carl Sagan? Clara Barton? Henry Ford? We should empower leaders who actually lead.

The reason that an elite group of brilliant experts has historically been antithetical to democracy is that it amounts to an elite of the few ruling the many. This model is like that of Ancient Sparta, empowering wise and accomplished people to come together and chart the course that would be best for all of us collectively. Our current democracy also has an “elite” but they do not boast the sort of qualifications that the people leading a nation that often fashions itself as the greatest in the world really deserves. Our tech-accelerated conception makes this irrelevant. Citizens vote on the bills directly, and the elite only keep their positions in the legislature if they are contributing to good (read: acceptable to the majority, as a democracy should be) legislation.

Now, for this solution to work would require some investments. 100% of all citizens who have the right to vote would need to own smartphones. The government would then need to provide comparable devices that are capable of properly handling the information review and secure voting process for those citizens who do not provide such devices for themselves. Additionally, there would need to be small, central voting stations in some geographic frequency to enable those with accessibility issues for whom the smartphone would not work to vote. While these represent significant new costs we would be retiring a myriad of old costs that, while I have been unable to find all of the data to provide a total cost rollup, is well into the billions of dollars each year spent by cities, counties, states and the federal government. The barrier to making this happen is not the cost; it is the collective will of those with vested interests who would lose their personal advantages for making this happen.

Let’s make it together.

Like many radical ideas, it may be seductive to focus on some vulnerability in it and try to pull it apart. Go ahead. This probably isn’t the exact right idea. But it’s a start down the right path. The digital world is nothing like the world that came before it, and we deserve it to ourselves and the future to rethink everything. Regardless of any issues with this system, I challenge you to make the case that, in their respective totalities, the current system is better than what’s proposed here. It isn’t.

Handheld Voting System

Overview

While a direct voting system is easily illustrated via the various screens that follow, the totality of the infrastructure would be immense. Such a system would likely fall under the auspices of the United States Department of Justice, incurring the bureaucratic trappings inherent in major government initiatives aimed at some 315 million people.

Bill Introduction

Citizens would periodically receive a bill to consider. Along with an overview of the bill, the first screen would display a graph showing the opinions of a personalized group of analysts, while “automagically” mapping each voter’s personal preferences to the content. While all voters would be encouraged to conduct their own research, the system would make it dead simple to see how the things they care about map to the specific legislation.

All information within the voting system would be available via written and audio means. Voters would have access to live helpers as well as brick-and-mortar voting centers for additional assistance.

Bill Overview

Protecting the integrity of the vote is a first-order priority, requiring the latest in identity recognition software. From a software development perspective, such security features would likely demand more ongoing investment than the entire rest of the system combined. This technology could also help customize the delivery and structure of information depending on its interpretation of a voter’s mood, attention, or other factors.

Simplified Overview Based on Comprehension

To further encourage voters’ critical thinking, the system would provide an interactive table of contents along with key statistics and graphs to aid understanding of essential aspects of the legislation.

The fine details of any national bill are bound to be complicated and potentially difficult to parse. A plain-language overview of the salient points would help citizens to understand what is at stake.

Analyst’s Response

While most citizens might be unable to read the entirety of bills, support would come from a new breed of political analysts. These individuals and organizations would read, interpret, and make recommendations on legislation based on their specific platforms and interests and provide citizens with their unique perspectives and voting recommendations.

Vote on the Bill

Voting time! The citizens would input their votes and let their voices be heard. The democratic process, as close to the ideal intention of this system, could be possible in a large, modern nation-state.

This article is also available as PDF, eBook, and spoken by the author free of charge.

Request a Copy

Comment on this article: